Hello, listeners! Welcome back to another exciting episode of “Dance Today!” I’m your host, Alex Short. Great news my friends! Today is a very special day for us here at the studio. This is actually the program’s 1,000th episode! I would like to take this opportunity to thank our amazing staff, who are constantly working behind the scenes to make the show the best it can be. Also, I’d like to thank you, the listeners, for your continued support and engagement. “Dance Today!” couldn’t happen without you guys. It’s listeners like you that have made this the most popular podcast in America for 7 consecutive years.

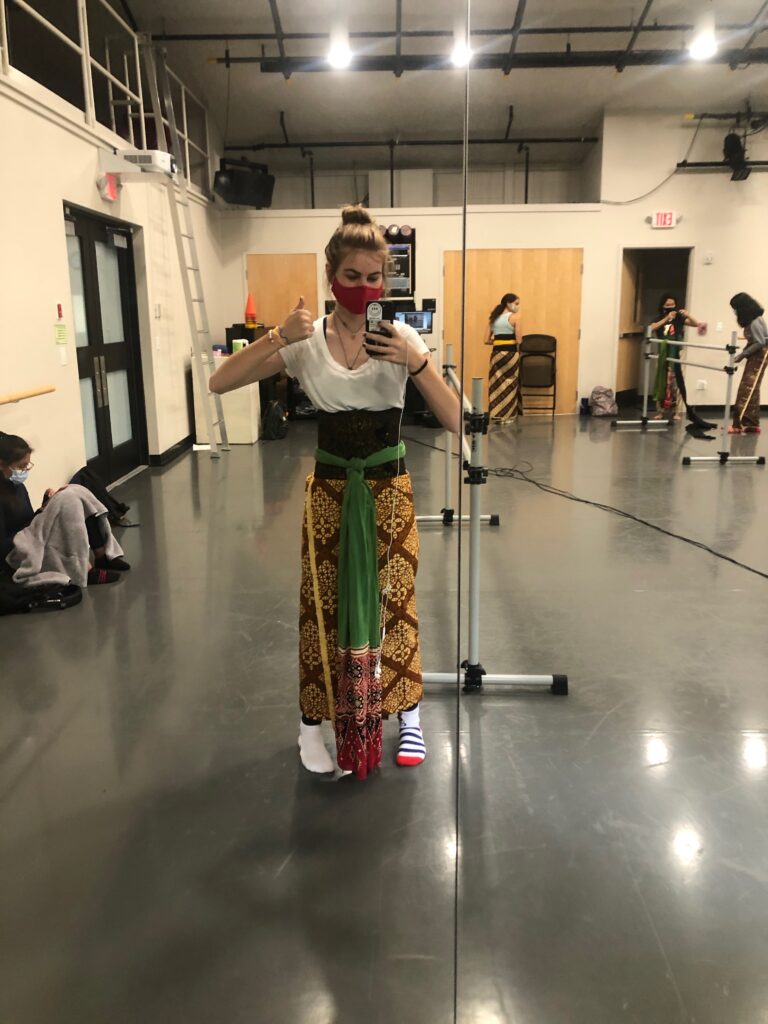

So, in honor of this special occasion, I’ve decided to talk about something very important to me. For about half a semester I have been studying Indonesian dance, with a focus on Javanese court dance. If you have no idea what this means, don’t worry! A mere half a semester ago I didn’t either. To clarify, Indonesian dance is a very broad term, as there are more than 3,000 dance styles that originated in Indonesia. I specify my experience is primarily with Javanese dance in an attempt to narrow down the vast world of Indonesian dance style. Java is an island within the diverse group of islands that make up the nation of Indonesia. Court dance is a very specific form of Javanese dance, however, as it originated in the courts of Yogyakarta and Surakarta. Obviously, that is not a complete explanation of court dance but will be sufficient for the purposes of this brief commentary. I will later discuss more about the cultural and political history of Indonesia. However, for now, I’d like to first examine the sensations of Javanese dance and articulate my personal experience in embodying it.

As I mentioned earlier, I have the most experience with Javanese court dance, in both practice and research. For those of you unfamiliar with this dance style, it is very slow and graceful, yet requires a great deal of strength. Most of the dance is done in “Mendhak,” which is similar to a deep squat or plie. Despite it being physically demanding, the dance must appear to the audience as effortless and delicate. It conveys a sense of refinement and inner peace known as “alus.” Alusness is characterized in the natural world as flowing water, which should give you a clue to the smooth and deliberate movements incorporated into court dance. Furthermore, Alusness is not exclusive to female style, even within the confines of the court. Male dancers are expected to convey alusness in addition to typical masculine power. Alusness is just one of the many requirements for court dancers, as dance is an incredibly respected and dignified practice in Java. A mirror of the reserved, composed nature of Javanese culture and social life, dance to is restrained. If a dancer is overly expressive or loose in their movements, it is considered rude and un-Javanese. This may come as a bit of a shock to any listeners who are used to the free, theatrical aspects of some Western dance styles.

Dancing the court style proved much more difficult than I anticipated. Capturing both delicateness and power at the same time was a real challenge for me. Yet, as I continued to practice, it began to feel much more natural in my body. Staying firmly rooted in Medhak and shifting my weight became much easier as my leg muscles got used to the movement. It wasn’t just muscle memory, though. The more time I put into each move, the more I understood the nuances behind them, feeling each joint and muscle slowly move into place. As my body began to understand, so did my mind. I was experiencing what court dancers feel in Java, a place I have never been to. The deliberation behind every step and the control and strength I had to maintain are both parts of everyday life and the general culture in Java. Physically embodying the cultural values of this place that is unfamiliar to me gave me a view into Javanese life, which combined with my academic research has helped me to better understand a completely different way of life from my own.

I wish I had been able to experience more different forms of dance within Indonesia, but most of my studies have been on Javanese style. This is in part due to the short nature of the Indonesian course I am taking, as we can only cover so much in a semester. However, there is another, more sinister reason. Unfortunately, during the time of “President” Suharto from 1967 –1998, various dance forms were lost. I realize the air quotes I just used for the word president are lost on our audio listeners, so I will clarify. Suharto was a president in title only, as he seized power from former president Sukarno and ruled as a dictator. His reign was violent and cruel, and he changed many key aspects of Indonesian life, including dance. While simultaneously promoting Javanese court dance and brutally snuffing out the many other diverse dances within Indonesia, Suharto was erasing cultures he saw as threatening. He popularized Javanese court dance because of the significance of the Sultan to the dance and inserted himself as the ruler the dance was honoring.

While this story of forced cultural expunction is tragic, in the time since Suharto’s presidency ended, there had been much progress towards teaching once forbidden dances to a new generation. I hope someday I will be able to experience those in the same way I have Javanese court dance.

Thanks for tuning in, that’s all for this week! Tune in next time, when I’m joined by the Queen of England to discuss tap dance!

Written by Alex Short

Categories

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||